Monochrome Woodcuts and Wood Engravings

In the late '20s, Walter J. Phillips became aware of a new trend among collectors away from colour prints to black and white prints. For several years, a stack of maple blocks in his possession had remained unused. The new popularity of black and white prints, combined with his desire to work up some of the sketches from his West Coast trip of 1926, led him to produce more prints in the wood engraving medium. The result was some of his most impressive work as a printmaker.

What distinguishes the wood engraving medium from that of the woodcut is the use of different wood and different tools. In wood engraving, the end-grain (cross-cut) is used instead of the plank-cut; the harder maple or boxwood is preferred for wood engraving rather than the usual fir or cherrywood of the woodcut. Engraving tools such as 'gravers,' needles, are used for finer detail, rather than the knives and gouges.

Wood engraving as a technique was well suited to commercial uses, because many impressions could be made without loss of definition. As a result, the blocks were 'type high' and could be set into a letter press. For several years, commercial illustration consisted principally of wood engravings. However, the wood engravings of Walter J. Phillips were, for the most part, a purely artistic endeavour, with prints produced in editions of 50 or just over 100.

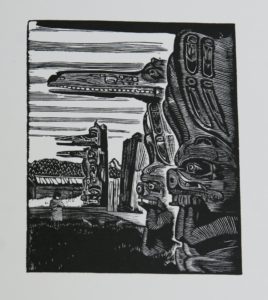

The sketchbook Phillips used during his West Coast trip shows how captivated he was with the totem poles he saw at Alert Bay, Karlukwees and New Vancouver (Tsatsisnukuomi). One drawing shows how faithfully he recorded the details of the poles; colour notations in the margin suggest that he considered using the subject for a colour woodcut.

In 1929 or 1930, it occurred to him that a selection of these sketches could be collected in a portfolio. An Essay in Woodcuts consists of 10 wood engravings and was issued in an edition of 120 in 1930. It is his most consistent portfolio, unified by medium and by subject matter. The print based on the drawing mentioned above is The Hoh-hok: House Posts at Karlukwees, the second print in the portfolio.

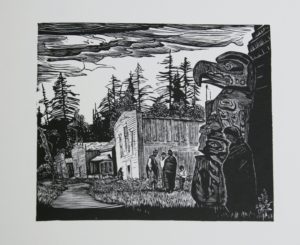

The 10th print, Community Houses, Mamalilicoola, is perhaps the most handsome of the set. A detail shows Phillips's use of the medium. With lines of various density, clarity is achieved with little apparent effort.

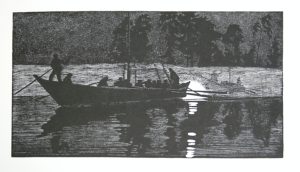

The following year, 1931, Phillips executed over 20 wood engravings for a small, not-so-limited edition book consisting of a lengthy poem by Robert Watson called Dreams of Fort Garry. Published by Stovels Company Ltd. of Winnipeg, 968 copies of the book were produced, as well as three sets of proofs. Once again, the strength of Phillips's graphic expression is evident. York Boats under Sail is an excellent example, exhibiting Phillips's attention to detail.

Moon and Mist, York Boats was produced in 1932, and can be numbered among the artist's great prints. The night scene is particularly appropriate for this essay in black. Lines and dots convey the different tones and textures of the subject in a most convincing way. In a brief preface to An Essay in Woodcuts, he stated that “no black is so rich and 'fat' as the black” in a wood engraving, “and no white is so pure. For graphic boldness, directness and simplicity,” Phillips thought the wood engraving was supreme.

The evidence of such consumate artistry makes one wonder why these wood engravings do not find as eager buyers nowadays as do the colour woodcuts. Phillips, a man of quiet humour, would no doubt be amused that collectors once again seem to prefer their prints coloured. Although he had abandoned the etching medium after a few years during the First World War, his interest in the black and white wood engraving medium was maintained. The last print he produced in 1952 was a small wood engraving entitled Bedtime, based on an earlier (1921) colour woodcut and sent as a Christmas greeting to family and friends that year.

Failing eyesight precluded the making of any more prints. He worked only in watercolour from then on, until total blindness afflicted him in 1960. He died in Victoria three years later.